PRINCIPLES

(See Chart of Principles at the close of this essay)

How can we tell if something is right or wrong? Can we assume that a thing is right if it is legal? But slavery was once legal; Nazism was legal. Can we assume a thing is right if it is endorsed by majority rule? But a lynch mob is majority rule. Is a thing sure to be right, then, if it comes about through the democratic process? But fascist dictator Juan Peron of Argentina was democratically elected by majority rule on two occasions. Hitler's grab for power was confirmed by a plebiscite. It appears that these various criteria all have their shortcomings.

Well, how about the Constitution? But again we run into difficulties, for the Constitution can be amended to say anything the majority wishes it to say. Suppose, for example, the Constitution were amended to permit the lynching of blacks – would this practice become acceptable merely because the Constitution permitted it?

And so the answer still eludes us. Where are the standards by which we can reliably determine what is right and what is wrong?

How about “the greatest good for the greatest number”? But does this popular slogan really constitute a sound principle? For example, what about the human sacrifices of the Mayans? The entire society achieved a sense of spiritual security at the expense of only one person. The “greatest good” of the French army was served by its refusal to admit its error in sentencing Captain Dreyfus to Devil's Island. In fact, the “greatest good for the greatest number” is served if a man is robbed and his property split among ten thieves!

So, what is right and what is wrong, and how do we decide? Do we flip a coin? Indeed, in a society ruled by “practical” politics, anything goes if enough people are for it. But the result is utter confusion: If a farmer were to seize the property of another we would call it stealing; but when the state performs this service for him we call it a “subsidy.” When one is compelled by force of law to serve the “Fatherland” we are repelled. Call it the “public interest,” however, and we are enraptured. The politician dispenses wealth that other men have produced, and we say he is “compassionate,” while the businessman who produces the wealth is dismissed as “greedy” and “materialistic.” If an individual were to impose a contract upon another by the threat of punishment, we would call it extortion; but if city hall does the deed, we call it “rent control.” If the majority violates the rights of the individual we call it injustice; if it has voted on the matter, however, we call it “democracy.”

When people have no clear idea of what is right and what is wrong; when they believe that everything is “relative,” they are headed for trouble. As Richard S. Wheeler once put it, “Today we abhor lampshades made of human skin; but tomorrow ... who knows? It is precisely those persons who are not anchored to a set of eternal values who hanker the most for novelties.”1

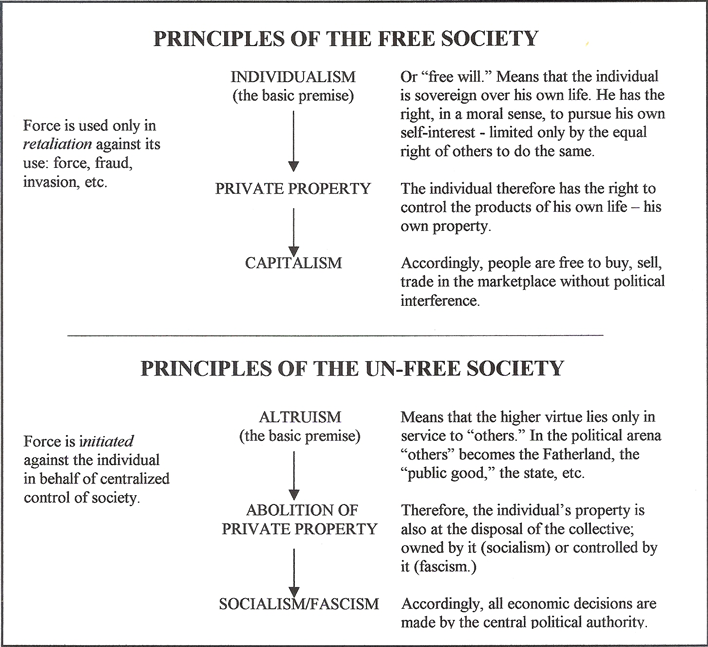

What is missing is principles, for these are the standards by which this or that issue can be evaluated. As pictured on the chart on the last page of this essay, the principles of the free society - as demonstrated by hundreds of years of hard-won experience - are individualism, the institution of private property, and capitalism, as we shall see. (By "capitalism" we do not mean, of course, the crony capitalism of today with government intervening at every opportunity, but rather an economy based on the voluntary exchange of the marketplace. The proper role of government is to be the referee, not the head coach or the play caller!)

ALTRUISM VS. INDIVIDUALISM

Cleveland industrialist James Finney Lincoln represented the best in American capitalism. When he died in 1965 he had been for nearly forty years president of the Lincoln Electric Company, the world's largest manufacturer of electric welding equipment. Back in 1934 Lincoln adopted what was at that time a highly unusual program: an employee incentive plan. The plan was so successful that, in the years that followed, the Lincoln Company was consistently able to undersell the competition while at the same time paying Lincoln employees nearly double the prevailing wages in the industry. The most intriguing part of the story, however, concerns the straightforward reason that James Lincoln gave for introducing the incentive program. “Selfishness,” he explained, “is the motivating force of all human endeavor.”

Lincoln obviously did not mean selfishness in the sense of concern for oneself “at the expense of others,” but rather the natural desire of most persons to act in their own rational self-interest by means of their own productive efforts. People are indeed selfish in this sense. They seek their own food, shelter, clothing, etc. If they did not, they would die. It's as simple as that. People will and should pursue their own welfare. Lincoln recognized this basic fact of nature and acted accordingly with results which were highly beneficial to all concerned.

The philosophical doctrine which recognizes the moral correctness of selfishness – as defined above – is called “egoism.” Individualism, a somewhat broader term, introduces the consequent relationship of the the individual to the group. Individualism maintains that the individual is justified in pursuing his own self-interest, and that, accordingly, he is not morally obligated to place the welfare of the “group” above his own. WEBSTER defines individualism as “The doctrine that the individual himself should be paramount in the determination of conduct; ethical egoism. The conception that all values, rights, and duties originate in individuals, and that the community or social whole has no ethical significance not derived from its constituent individuals.”

Upon the premise of individualism the rest depends. If it is accepted, the remaining principles – private property and capitalism – inescapably follow. If the opposing premise is adopted, however, then the institution of private property will be rejected and the result will be some form of socialism or fascism.

And what is the opposing premise? According to the dictionary the philosophical opposite to individualism is altruism. WEBSTER defines altruism as “regard for and devotion to the interests of others as an ethical principle,” and goes on to quote the DICTIONARY OF POLITCAL ECONOMY as stating: “Altruism is an ethical term ... opposed to individualism or egoism ... and embraces those moral motives which induce a man to regard the interests of others.”

But what is wrong with having regard for the interests of others? Nothing, in itself. Charity, for example, is an important part of any civilized society. But the individualist would donate in response to his own values while the altruist would feel obliged to place the values of others above his own. This is no mere quibble in semantics. It is the difference between black and white, and the premise one adopts will establish one's attitude on every social and political issue ever raised.2 There can be no coherent middle ground, for any attempt at holding two opposing premises at the same time will lead only to confusion and contradiction.

The word that best describes the morality of altruism is “sacrifice.” Self-sacrifice for the sake of others is, in a nutshell, the altruist ideal. But there are sacrifices and there are sacrifices, and the crucial distinction should be made: sacrifice for whose ultimate benefit?

Does the individual gain or lose by his sacrifice? For example, a parent might give up a new suit in order to buy his child a bicycle. But the parent has not lost in the bargain, for his child's happiness is (evidently) of greater value to him than the suit. Similarly, when the priest dedicates his life to the church it is probably because this vocation brings a sense of fulfillment to his own life.

(Yet, the altruist philosopher Emmanuel Kant would evidently deny that there was moral worth in either of these actions since the parent and the priest were both acting for selfish reasons! According to Kant, an act has moral worth only if done out of a sense of duty. In his METAPHYSICS OF MORALS he gives the example of the tradesman who deals honestly with his customers, “but this is not enough to make us believe that the tradesman has so acted from duty and from principles of honesty: his own advantage required it...Accordingly the action was done merely with a selfish view.”)

Altruism, with its emphasis on self-sacrifice, is not a healthy moral code. Still, many people, beguiled by what they feel is a doctrine of humanitarian benevolence, think of themselves (or would like to think of themselves) as altruists. John Stuart Mill, for example, writes in his essay UTILITARIANISM that “[Only in an imperfect world can man] best serve the happiness of others by the absolute sacrifice of his own [happiness]. Yet as long as the world is in that imperfect state, I fully acknowledge that the readiness to make such a sacrifice is the highest virtue ... self renunciation ... devotion to the happiness ... of others.”

Yet, from Mill's altruistic statement one must conclude that the most virtuous person of all would be the slave! Is it not the slave who is sacrificing to the greatest degree his own happiness for the good of others? But Mill no doubt meant that the sacrifice must be voluntary. All right then, it is the willing slave whose actions would be, according to Mill, the most virtuous: it is the slave who says, “Master, you can remove the chains, and I will not run away, for I now realize that true virtue lies in sacrificing my happiness to yours.” If you still think you are an altruist, consider the following situation: suppose your house and your neighbor's house are both on fire, and suppose the situation is such that you can save only one of them. Which house would you save? Surely you would – or should – save your own. Altruism, however, urges selfless devotion to the interests of others. Altruism requires, then, that you save your neighbor's house and let your own burn. Do you still think you are an altruist?

If you still think you are an altruist, then good luck – because you will be the patsy for every user, parasite, exploiter, con-artist and compassion-mongering politician that comes along. The genuine altruist – if there could really be such a thing – voluntarily enslaves himself to the needs, whims and demands of every other person!

Even as a guide for purely personal conduct it should be apparent that altruism is not a healthy moral code. But it is when altruism serves as the underlying premise of a political doctrine that the real trouble begins. True virtue still lies in service to “others,” but “others” now means some empty political abstraction such as “society” or the state or the “public interest,” or whatever. Most of the political philosophers in history have based their arguments on one form or another of the altruist premise, and at best the result has been total confusion. The Roman emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius, for example, wrote in his MEDITATIONS that “that which does no harm to the State does no harm to the citizen ... “ But would it have been true, let us say, in Nazi Germany that “that which does no harm to the State does no harm to the citizen”? Aurelius goes on to say, “For whatsoever either by myself or with another I can do, ought to be directed to this only, to that which is useful and well suited to society.”

Most people today would quickly agree with this noble- sounding altruistic sentiment. But suppose the society in question were a society of cannibals? Should the individual leap into the cooking pot joyful in the knowledge that he was achieving true virtue by doing that which was “useful and well suited to society”? Once one adopts the self-sacrificial morality of altruism the concept of individual rights is totally obscured, and it should be apparent that the result is ideological chaos.

At best a political philosophy based on the premise of altruism leads to confusion. At worst, it leads to tyranny. “To be a socialist,” declared Nazi socialist Joseph Goebbels, “is to submit the I to the thou; socialism is sacrificing the individual to the whole.”3 Stalin was equally explicit in asserting that true virtue lay in self-sacrifice to the collective:

True Bolshevik courage does not consist in placing one's individual will above the will of the Comintern. True courage consists in being strong enough to master and overcome oneself and subordinate one's will to the will of the collective, the will of the higher party body. 4

In either of the above statements the underlying premise is the same. But the doctrine of self-sacrifice is no longer in the ivory tower – it has entered the political arena, and the philosophical “thou ought” has finally become the legislated “thou must.” What was previously only a “moral obligation” has now become a “duty.” Every tyranny in history has been based on some variation of this theme. Under Stalin and Lenin it was the duty of the individual to serve the proletariat. Under Hitler it was the Fatherland. Under Mussolini it was the State. The altruist ideal of service to some “greater good” is the cornerstone of tyranny.

But does the dictator himself believe in the altruism that he preaches? Whether he does or doesn't is not important. Altruism serves as the premise of tyranny not because the leader accepts it but because his subjects accept it. Perhaps they accept it grudgingly, but they still accept it. When Hitler shouted that it was the duty of the good German citizen to sacrifice for the Fatherland, he would have shouted in vain were it not that too many good German citizens had been brought up to believe precisely that. And as long as people continue to believe that true virtue lies in subordinating oneself to some “greater good,” there will continue to be dictators to see that virtue prevails.

PRIVATE PROPERTY

If the premise of individualism is accepted, then the institution of private property cannot be denied, for it could not be argued with any coherence that the individual has the right to his own life, but not to the products of it. If the opposing premise of altruism is adopted, however, then the institution of private property will be rejected – for when it is the duty of the individual to serve others, then the products of his life are equally at their disposal. But the premise of altruism is unworkable and unlivable, and those societies which have attempted to abolish private property have invariably stagnated. The experience of the first Plymouth Colony provides eloquent testimony to the unworkability of collective ownership of property. In his history of the Plymouth Colony, Governor Bradford described how the Pilgrims farmed the land in common, with the produce going into a common storehouse. For two years the Pilgrims faithfully practiced communal ownership of the means of production. And for two years they nearly starved to death, rationed at times to “but a quarter of a pound of bread a day to each per- son.” Governor Bradford wrote that “famine must still ensue the next year also, if not some way prevented.” He described how the colonists finally decided to introduce the institution of private property:

[The colonists] begane to thinke how they might raise as much corne as they could, and obtaine a beter crope than they had done, that they might not still thus languish in miserie. At length [in 1623] after much debate of things, the Gov., with the advice of the cheefest amongest them, gave way that they should set downe every man for his owne perticuler, and in that regard trust to themselves .... And so assigned to every family a parceel of land ....

This had very good success; for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corne was planted than other waise would have bene by any means the Gov. or any other could use, and saved him a great deall of trouble, and gave farr better contente. The women now wente willingly into the field, and tooke their litle-ons with them to set corne, which before would aledge weakness, and inabilitie; whom to have compelled would have bene thought great tiranie and opression.

Reflecting on the experience of the previous two years, Bradford goes on to describe the folly of communal ownership:

The experience that was had in this commone course and condition, tried sundrie years, and that amongst godly and sober men, may well evince the vanitie of that conceite of Platos and other ancients, applauded by some of later times; - that the taking away of propertie, and bringing in communitie into a commone wealth, would make them happy and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God. For this comunitie (so farr as it was) was found to breed much confusion and discontent, and retard much imployment that would have been to their benefite and comforte. For the yong-men that were most able and fitte for labour and service did repine that they should spend their time and streingth to worke for other mens wives and children, with out any recompense. The strong, or man of parts, had no more in divission of victails and cloaths, than he that was weake and not able to doe a quarter the other could; this was thought injuestice …

The colonists learned about “the wave of the future” the hard way. However, once having discovered the principle of private property, the results were dramatic. Bradford continues:

By this time harvest was come, and instead of famine, now God gave them plentie, and the face of things was changed, to the rejoysing of the harts of many, for which they blessed God. And the effect of their perticular [private] planting was well seene, for all had, one way and other, pretty well to bring the year aboute, and some of the abler sorte and more industrious had to spare, and sell to others, so as any generall wante or famine hath not been amongest them since to this day.

Communal ownership of property had been tried and it had failed. Even among “godly and sober men” it was at best a marginal system. Only when the institution of private property was introduced did the colonists achieve abundance.

The experience of the Plymouth Colony has been repeated in the present day by the communal settlements of Israel. The heavily-subsidized kibbutzim were never the shining successes which socialists elsewhere dreamed them to be. As Daniel Doron, director of a Tel Aviv think tank writes,

[They] used to be the intellectual and social avant-garde of Israel, shaping its anti-capitalist and anti-profit bias. They are now burdened with $2 billion in debt and seem to be economically unviable now that high government subsidies have been reduced. About half the young people in these settlements are leaving. A grandchild of Israel's fist kibbutz founder and chief ideologue has even called for reforming the kibbutz along the lines of “enlightened capitalism.” The old egalitarian system encouraged sloth and waste and punished enterprising members, he said.5

Private property is more than the key to material abundance, however. It is the cornerstone of the free society. Without property rights no other rights can be secure. Freedom of religion, for example, is impossible where church property is owned or controlled by the state. Freedom of assembly is equally a fiction if all gathering places are under state control. The communist bloc countries supposedly enjoy a measure of free speech, but since the paper mills and printing presses and publishing houses are all owned by the state, there is no means by which dissenting views can be readily circulated. These civil rights, even if nominally observed, are not really rights at all, since their exercise is conditional, depending ultimately upon state approval and cooperation. It's worth noting that the Soviet Constitution listed all of the familiar civil rights – except the basic right of private property without which the others cannot be exercised in any meaningful form. Only when property rights are respected can the other rights be secure.

CAPITALISM

Not so many years ago it was a matter of heated debate which was the more productive system, capitalism or socialism. Today, however, with socialism generally in retreat around the globe, few people outside the ivory towers of academia seriously argue the point. Materially, capitalism is acknowledged to be the hands-down winner. Case closed.

Unfortunately, however, the case is not closed. If people are convinced (as many are) that capitalism is morally repugnant because it is based on “selfishness,” and “private greed,” they will oppose it vehemently, productive or not.

And so we are brought full circle to the first issue of this discussion: the philosophical premise on which the entire capitalism/socialism debate hinges. Socialism, based on the altruist premise of “service to others” is “unselfish.” Capitalism, based on the individualist premise of self-interest, is driven by "greed" and "selfishness." But which is really the immoral system?

It is argued here that altruism, an irrational and unlivable concept, is in fact the immoral (i.e., destructive of life) doctrine. Moreover, when it enters the political arena, it leads inexorably to tyranny. In contrast, individualism is entirely consistent with a productive and rational human nature, and from this premise private property and capitalism inescapably follow.

PRINCIPLES AND THE POOR

Because the theme of this book has been the perverse impact upon the poor of various programs and ideologies, perhaps we should return to that point. What happens to the poor in a society based on self-interest? Capitalism is admittedly more productive – but are the benefits reserved exclusively for those with a secure spot on the economic ladder? Evidently not, for few would deny that the gap between rich and poor is far narrower in the “selfish” capitalist countries that in the “unselfish” collectivist societies. Call it “trickle down” perhaps, but the reality is that there is a far bigger trickle in the former than in the latter.

The more important issue in the overall problem of poverty, however, is not what trickles down, but the opportunity to move up: access to the all-important first rung of the economic ladder. But as we will see in the essay “The War Against the Poor,” a major obstacle to achieving that first rung is interventionist government! There will never be a “final solution” to the problem of poverty, for some will always be (materially) worse off than others, no matter what system is employed. But the optimum system will be that which maximizes economic opportunity for all, and that system is the free and open society – and its guiding principles are individualism, private property, and capitalism.

(See the chart below)

|

***

Footnotes

1) Richard S. Wheeler, "Lead Us Not Into Tempation," INSIGHT AND OUTLOOK (1960)

2) It was novelist-philosopher Ayn Rand who demonstrated most forcefully the significance of

the conflict between these two diametrically opposed concepts.

3) Cited by Arthur Schlesinger, THE VITAL CENTER, (HOUGHTON-MIFFLIN Co. 1962, P. 54.

4) Ibid. p. 56.

5) Daniel Doran, "A Sea Change In Israel," 1984-1988" WALL STREET JOURNAL, Oct. 28, 1988, Op. Ed. page.